Recent Bank Runs and the Need for a Permanent Transaction Account Guarantee Program

March 22, 2023

Introduction

As we have been urging since 2020,1 and in light of the recent failures of Silicon Valley Bank (“SVB”) and Signature Bank, the industry needs a permanent transaction account guaranty program (“TAGP”).2 The TAGP was originally tucked within the Temporary Liquidity Guarantee Program (the “TLGP”) during the subprime crisis era. A permanent TAGP would curb depositor fears and prevent future bank runs, rather than utilizing ex post facto remedies, such as the systemic risk exception (“SRE”) in response to bank failures.

Spooked by the abrupt collapse of SVB and Signature Bank, consumers and business owners are fleeing to the perceived safety of large institutions—those “too big to fail.”3 Further, as customers withdraw funds in efforts to run to safety, regional banks will “need to pay more for funding, either by raising interest rates on deposits or by paying higher lending costs in the wholesale market.”4 According to Bank of America Global Research, “[a]bsent a change to deposit insurance coverage, corporate CFOs/Treasurers will likely be proactively looking to diversify their deposits away from any single institution.”5 Therefore, financial institutions of all sizes can expect to be impacted.

The shock of deposit outflows is apparent on Federal Home Loan Banks (“FHLBs”) as well, as Goldman Sachs research found that FHLBs have

seen a dramatic pick up in money market fund flows usage. FHLB bond issuance reached $385bn over three days this past week vs. between $400-600bn annually from 2019-2022. The discount window and the new Bank Term Funding Program, or BTFP, saw a combined usage of ~$160bn of uptake this past week vs. $5bn of total usage in the prior week, and there was a separate, additional $143bn of Fed balance sheet usage by SVB and Signature Bank.6

The Morning Consult poll suggested that “14% of people have moved some or all of their money as a result of SVB.”7 Such a shift of deposits may lead to “greater consolidation of the U.S. banking industry”8 and further destabilize the market, absent implementation of a permanent TAGP.

During the financial crisis in 2008, the FDIC established the TLGP. The TLGP was considered an integral part of the broad government response to systemic risk in the banking system at that time, and it was the first time in the FDIC’s history that it protected uninsured deposits and bank debt. At its height, the FDIC guaranteed approximately $350 billion in newly issued bank debt and $800 billion in deposits under the program.9 As a result of changes in applicable law as part of the Dodd-Frank Act, the FDIC’s authority to implement a liquidity guaranty program similar to the TLGP has been limited. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Congress temporarily restored the FDIC’s power to institute a program like the TLGP, although the FDIC did not do so.

The TLGP was established pursuant to the SRE. In response to the banking crisis of the 1980s and early 1990s, Congress implemented the SRE into the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Improvement Act of 1991 (“FDICIA”). The SRE is an exception under which the FDIC may take certain actions that may not be the “least costly” to taxpayers but avoid or mitigate the adverse effects of paying for the least costly resolution method on the “backs of uninsured depositors.” Thus, it permits the FDIC to take certain actions when it determines that a situation poses a serious financial market risk to the US banking system as a whole. In order to invoke the exception, the FDIC and Federal Reserve Board must recommend it, and the Secretary of the Treasury, in consultation with the President, must agree with the recommendation. Unless the SRE were invoked, the FDIC was required to help troubled institutions in a method that minimized the cost to the Deposit Insurance Fund (“DIF”). The exception has only been used three times until recently: it was used to resolve three of the four largest bank failures in late 2008 and early 2009. On March 12, 2023, the FDIC and the Federal Reserve announced that the FDIC would cover the full amount of accounts on deposit at both SVB and Signature Bank, pursuant to the SRE.

This client alert revisits the TLGP implemented by the FDIC from 2008-2012 and discusses the potential benefits of the TLGP as a permanent program as compared to ex post facto remedies, such as the SRE.

Again, the TLGP consisted of two components, the Debt Guarantee Program (“DGP”) and the TAGP. The DGP guaranteed new senior unsecured debt issued by financial institutions and their holding companies. The TAGP, which is the focus of this client alert, guaranteed in full certain eligible accounts and was intended to reestablish confidence in banks and prevent bank runs.

Transaction Account Guarantee Program

Through the TAGP, the FDIC fully guaranteed noninterest bearing transaction accounts (“NIBTAs”), Interest on Lawyers Trust Accounts (“IOLTAs”), and low-interest negotiable order of withdrawal (“NOWs”) at FDIC-insured financial institutions. The TAGP was intended to comfort depositors in order to avoid runs at healthy banks. The TAGP was the first instance when the FDIC ever extended unlimited deposit insurance protection to a class of bank deposits. Small-business accounts were specifically targeted because the FDIC found these types of accounts frequently exceeded the standard $250,000 insurance limit. The purpose of the TAGP was to strengthen confidence and encourage liquidity in the banking system.

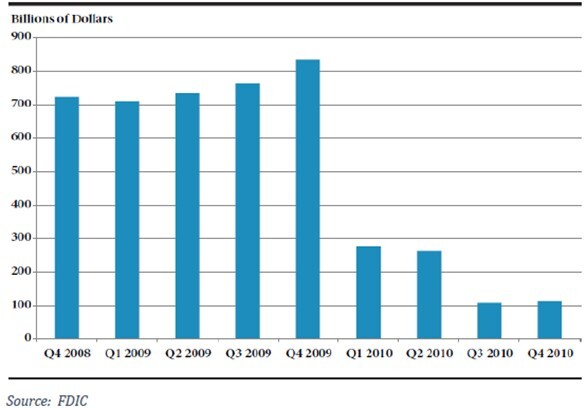

Amounts Guaranteed by TAGP, 2008-2010

The TAGP covered all non-interest-bearing transaction deposits above the FDIC’s standard insurance limit, $250,000. Based on industry comments, the FDIC extended the TAGP to cover accounts considered important to sole proprietorships and charitable organizations and permitted participating institutions to maintain rates up to an initial 50 basis points (eventually lowered to 25 basis points as part of the second extension of the program). All FDIC-insured institutions were automatically enrolled in the TAGP, free of charge, with the option to opt out after 30 days. After 30 days, the TAGP imposed fees for participating in the program consisting of a 10 basis point annual assessment rate surcharge on qualifying accounts for amounts over $250,000. The FDIC later increased the fees—15, 20 or 25 basis points—charging a higher annualized rate depending on the risk category assigned to an institution in the FDIC’s risk-based premium system, partly to limit losses associated with the program.10 The risk based determinations were made using the FDIC’s risk-based premium system, which considered a bank’s size, capital adequacy, asset quality, management, earnings, liquidity and sensitivity. The FDIC mandated all eligible institutions to disclose to customers whether they were participating in the TAGP, including through lobby notices and through website notices.

Eighty-six percent of banks remained in the TAGP after 30 days. The FDIC extended the TAGP twice through December 31, 2010. The Dodd-Frank Act replaced the TAGP with a similar program, which the FDIC administered. This statutory extension ended on December 31, 2012. Through 2010, the TAGP collected $1.2 billion in fees and covered over $834 billion in deposits. The FDIC absorbed $1.5 billion in losses from the failure of banks covered by the TAGP.

In an echo to today’s issues, the FDIC credits the TAGP for preventing disruptive shifts in deposit funding for participating institutions. The program provided banks with an additional source of funding and stabilized deposit funding. Further, the TAGP also aided in reducing administrative costs of the FDIC in resolving banks, as the extensive insurance coverage meant it did not have to identify which deposits were insured and which were not. Best of all, small business owners and their employees were not left holding the proverbial bag.

To enroll in the TAGP, institutions had to provide the FDIC with information regarding eligible accounts—those eligible accounts with deposits exceeding $250,000. Using such information, the FDIC determined the fees that an institution would pay to participate in the program. These fees permitted the FDIC to fund the TAGP without using the DIF or taxpayer funds. If the fees were unable to cover bank defaults, the FDIC intended to cover the difference with a special assessment fee—a fee charged to the banking industry to cover losses. The result may be the same dollars as with the use of the SRE but without the frontend disruption. Ultimately, no special assessment fee was ever imposed, as profits from the DGP covered the TAGP’s losses.

The TAGP was originally meant to cover NIBTAs, given that these accounts did not bear any interest. Upon receiving feedback from depositors and institutions, the FDIC extended the program to cover NOW accounts that bore low interest rates and later to include IOLTAs. However, given that restrictions on paying interest on deposits are no longer an issue, we believe any future TAGP program should cover interest bearing transaction accounts.

Several of our clients have seen an increase in cash demands from customers who are wary of having uninsured funds at their financial institution. Had the TAGP been in place weeks ago, SVB and Signature Bank may be alive today, and other banks would not be facing deposit runs from thousands of companies worrying about their financial solvency. Reimplementation of a permanent version of the TAGP would maintain depositor confidence, and thus provide a framework to prevent bank runs long term. Any program, however, should cover interest bearing accounts in addition to the other accounts eligible under the original rule.

Systemic Risk Exception

While the TAGP was established pursuant to the SRE, the use of the SRE for Signature Bank and SVB differs from the TAGP. While the recent application of the SRE is an ad hoc response to an emergency, the TAGP is a framework designed to ward off such liquidity meltdowns from ever materializing. Customers cannot rely on a retroactive application of the SRE. Thus, an after-the-fact approach to application of the SRE just ensures there will be more applications of the SRE needed. Customers are not willing to wait around for such a possibility. In other words, using the SRE as a backdated fit is inherently destabilizing.

Although systemic importance is not based on size, it is correlated with size—it is hard to imagine any truly small financial institution being systemically important. Nonetheless, banks that are not considered systemically important, such as community banks, must pay the bill to cover bank runs in increased deposit assessments, despite not being afforded similar protections. This is illustrated through the FDIC’s failed bank database, which consists of various depositors in smaller failed banks that often lost half or more of their uninsured balances. Such small institutions were not deemed systemically important; thus, their customers did not receive government protection.

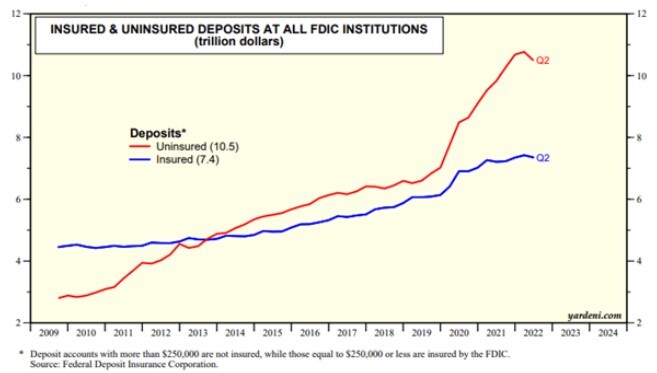

Below is a chart comparing insured and uninsured deposits for all FDIC institutions.

As of 2022, uninsured deposits at FDIC institutions had increased to $10.5 trillion. However, FDIC institutions only had $7.4 trillion in insured deposits. The large gap between the two amounts illustrates an issue that regulators must address going forward.

While the same $250,000 insurance limit applies to accounts at such larger institutions, there is widespread belief that either the government would never permit such large banks to fail due to the systemic risk involved, or alternatively, as we have recently seen in one notable recent instance, the large institutions will rally together in efforts to add to deposit funding to save institutions. However, such ad hoc measures cannot be anticipated or relied on by depositors, as they are merely an exercise in brinkmanship.

Given the increase of uninsured deposits compared to insured deposits, a program similar to the TAGP should be implemented to restore customer confidence. Such a program will prevent bank runs in the long term and provide protection to institutions of all sizes. While a permanent TAGP would involve institutions paying increased deposit assessments, those “non-systemically important” institutions would receive deposit protection beyond the $250,000 limit.

Conclusion & Next Steps

The SRE was recently used to cover noninsured deposits of SVB and Signature Bank. However, a permanent TAGP that extended to interest bearing accounts would guarantee deposits of institutions not deemed systemically important, thus preventing fears systemwide and also prevent favoritism through bank runs to large, systemically important banks and away from community banks.

In light of SVB and Signature Bank, depositor fears are acute. We believe the FDIC should move quickly to exercise its authority and implement a permanent liquidity guarantee program to allay depositor fears and prevent the need for ex post facto remedies like the SRE.

***

How We Can Help: Hunton Andrews Kurth LLP has assembled a cross-disciplinary team consisting of attorneys from our bank regulatory, finance, structured finance and securitization, capital markets, securities, private equity/VC, M&A, employers’ rights, insurance, real estate, and bankruptcy, restructuring and creditors’ rights practices to assist clients with the unfolding situations involving Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank and any similarly situated banks.

Please contact any of the attorneys listed on this Client Alert, any other attorney you regularly work with at Hunton, or reach out via email to HuntonTroubledBankTaskForce@huntonak.com, to be connected with our team monitoring and helping clients respond to these issues and continuing developments.

Resources:

- Vergara, Ezekiel, 2022. “United States: Transaction Account Guarantee Program,” Journal of Financial Crises, Yale Program on Financial Stability (YPFS), vol. 4(2), pages 673-693, April.

- FDIC Temporary Liquidity Guarantee Program Frequently Asked Questions

- Crisis and Response, An FDIC History, 2008-2013, Chapter 2 —The Temporary Liquidity Guarantee Program.

2 Peter Weinstock, ‘Moral hazard’ is an outdated concept. SVB and Signature prove it (March 16, 2023). In response to Mr. Weinstock’s Op Ed piece, the CEO of a well-capitalized and high performing regional bank said,

[m]oral hazard should exist for all creditors, trading counterparties, bondholders, and equity holders of a financial institution, but not depositors. Even the most sophisticated financial analysts like the rating agencies could not predict and rate for the recent events that transpired. It is unreasonable to expect any depositor to be in a position to evaluate the financial strength of their bank. We don’t blame the patient for a botched surgery because they failed to properly research the surgeon. Similarly, it is difficult to create true moral hazard here by insuring all deposits. There are a lot of moving parts that have transpired since the Great Financial Crisis beyond the too-big-to fail designations. Social media exaggerates the ability of a bad actor to yell fire in a crowded theater. The swift ability to move money electronically without any friction at all is also very different. In 2008 a depositor had to call a bank employee to initiate a wire. That created an opportunity for a thoughtful conversation. That “friction” is largely gone today, and money moves quickly with little ability by the bank to influence irrational thought. Technology has also brought a complex web of inter-bank solutions to sharing large deposit insurance risk and will ultimately make the workout of troubled banks more complicated. These are all reasons why full deposit insurance makes sense. The regulatory framework needs to adjust to account for unintentional consequences from the Great Financial Crisis while also considering the modern world of how quickly money moves.

3 David J. Lynch, Panic Feeds Biggest Banks, Dallas Morning News (March 20, 2023).

4 Id.

5 BoA Global Research, the Flow Show, the Perfect Low (March 16, 2023).

6 Goldman Sachs, Americas Banks: An update on key questions across the banking system (March 19, 2023).

7 Goldman Sachs, Americas Banks: An update on key questions across the banking system (March 19, 2023).

8 David J. Lynch, Panic Feeds Biggest Banks, Dallas Morning News (March 20, 2023).

9 https://www.fdic.gov/bank/historical/crisis/chap2.pdf

10 FIL-48-2009.